1936–1939 Arab revolt in Palestine

| 1936–1939 Arab revolt in Mandatory Palestine | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the intercommunal conflict in Mandatory Palestine, the decolonisation of Asia, and the precursor to the Israeli–Palestinian conflict | |||||||

British soldiers on an armoured train car with two Palestinian Arab hostages used as human shields. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

NDF (from 1937)

|

Arab Higher Committee (1936–October 1937)

Central Committee of National Jihad in Palestine (October 1937 – 1939)

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

Political leadership: Local rebel commanders: Sa'id al-'As † | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

25,000[1]–50,000[2] British soldiers 20,000 Jewish policemen, supernumeraries and settlement guards[3] 15,000 Haganah fighters[4] 2,883 Palestine Police Force officers(1936)[5] 2,000 Irgun militants[6] |

1,000–3,000 (1936–37) 2,500–7,500 (plus an additional 6,000–15,000 part-timers) (1938)[7] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

British Security Forces: 262 killed c. 550 wounded[8] Jews: c. 500 killed[9] 2 executed |

Arabs: c. 5,000 killed[1] c. 15,000 wounded[1] 108 executed[8] 12,622 detained[8] 5 exiled[8] | ||||||

A popular uprising by Palestinian Arabs in Mandatory Palestine against the British administration, later known as the Great Revolt,[a][10] the Great Palestinian Revolt,[b][11] or the Palestinian Revolution,[c] lasted from 1936 until 1939. The movement sought independence from British colonial rule and the end of British support for Zionism, including Jewish immigration and land sales to Jews.[12]

The uprising occurred during a peak in the influx of European Jewish immigrants,[13] and with the growing plight of the rural fellahin rendered landless, who as they moved to metropolitan centres to escape their abject poverty found themselves socially marginalized.[14][d] Since the Battle of Tel Hai in 1920, Jews and Arabs had been involved in a cycle of attacks and counter-attacks, and the immediate spark for the uprising was the murder of two Jews by a Qassamite band, and the retaliatory killing by Jewish gunmen of two Arab labourers, incidents which triggered a flare-up of violence across Palestine.[16] A month into the disturbances, Amin al-Husseini, president of the Arab Higher Committee and Mufti of Jerusalem, declared 16 May 1936 as 'Palestine Day' and called for a general strike. David Ben-Gurion, leader of the Yishuv, described Arab causes as fear of growing Jewish economic power, opposition to mass Jewish immigration and fear of the British identification with Zionism.[17]

The general strike lasted from April to October 1936. The revolt is often analysed in terms of two distinct phases.[18][19] The first phase began as spontaneous popular resistance, which was seized on by the urban and elitist Arab Higher Committee, giving the movement an organized shape that was focused mainly on strikes and other forms of political protest, in order to secure a political result.[20] By October 1936, this phase had been defeated by the British civil administration using a combination of political concessions, international diplomacy (involving the rulers of Iraq, Saudi Arabia, Transjordan and Yemen)[21] and the threat of martial law.[22] The second phase, which began late in 1937, was a peasant-led resistance movement provoked by British repression in 1936[23] in which increasingly British forces were targeted as the army itself increasingly targeted the villages it thought supportive of the revolt.[24] During this phase, the rebellion was brutally suppressed by the British Army and the Palestine Police Force using repressive measures that were intended to intimidate the whole population and undermine popular support for the revolt.[25] A more dominant role on the Arab side was taken by the Nashashibi clan, whose NDP party quickly withdrew from the rebel Arab Higher Committee, led by the radical faction of Amin al-Husseini, and instead sided with the British – dispatching "Fasail al-Salam" (the "Peace Bands") in coordination with the British Army against nationalist and Jihadist Arab "Fasail" units (literally "bands").

According to official British figures covering the whole revolt, the army and police killed more than 2,000 Arabs in combat, 108 were hanged,[8] and 961 died because of what they described as "gang and terrorist activities".[26] In an analysis of the British statistics, Walid Khalidi estimates 19,792 casualties for the Arabs, with 5,032 dead:[e] 3,832 killed by the British and 1,200 dead due to intracommunal terrorism, and 14,760 wounded.[26] By one estimate, ten percent of the adult male Palestinian Arab population between 20 and 60 was killed, wounded, imprisoned or exiled.[28] Estimates of the number of Palestinian Jews killed are up to several hundred.[29]

The Arab revolt in Mandatory Palestine was unsuccessful, and its consequences affected the outcome of the 1948 Palestine war.[30] It caused the British Mandate to give crucial support to pre-state Zionist militias like the Haganah, whereas on the Palestinian Arab side, the revolt forced the flight into exile of the main Palestinian Arab leader of the period, al-Husseini.

Economic background

World War I left Palestine, especially the countryside, deeply impoverished.[31] The Ottoman and then the Mandate authorities levied high taxes on farming and agricultural produce and during the 1920s and 1930s this together with a fall in prices, cheap imports, natural disasters and paltry harvests all contributed to the increasing indebtedness of the fellahin.[32] The rents paid by tenant fellah increased sharply, owing to increased population density, and growing transfer of land from Arabs to the Jewish settlement agencies, such as the Jewish National Fund, increased the number of fellahin evicted while also removing the land as a future source of livelihood.[33] By 1931 the 106,400 dunums of low-lying Category A farming land in Arab possession supported a farming population of 590,000 whereas the 102,000 dunums of such land in Jewish possession supported a farming population of only 50,000.[34] The late 1920s witnessed poor harvests, and the consequent immiseration grew even harsher with the onset of the Great Depression and the collapse of commodity prices.[13] The Shaw Commission in 1930 had identified the existence of a class of 'embittered landless people' as a contributory factor to the preceding 1929 disturbances,[35] and the problem of these 'landless' Arabs grew particularly grave after 1931, causing High Commissioner Wauchope to warn that this 'social peril ... would serve as a focus of discontent and might even result in serious disorders.'[35] Economic factors played a major role in the outbreak of the Arab revolt.[14] Palestine's fellahin, the country's peasant farmers, made up over two-thirds of the indigenous Arab population and from the 1920s onwards they were pushed off the land in increasingly large numbers into urban environments where they often encountered only poverty and social marginalisation.[14] Many were crowded into shanty towns in Jaffa and Haifa where some found succour and encouragement in the teachings of the charismatic preacher Izz ad-Din al-Qassam who worked among the poor in Haifa.[14] The revolt was thus a popular uprising that produced its own leaders and developed into a national revolt.[14]

Although the Mandatory government introduced measures to limit the transfer of land from Arabs to Jews, these were easily circumvented by willing buyers and sellers.[35] The failure of the authorities to invest in economic growth and healthcare for the general Palestinian public and the Zionist policy of ensuring that their investments were directed only to facilitate expansion exclusively of the Yishuv further compounded matters.[36] The government did, however, set the minimum wage for Arab workers below that for Jewish workers, which meant that those making capital investments in the Yishuv's economic infrastructure, such as Haifa's electricity plant, the Shemen oil and soap factory, the Grands Moulins flour mills and the Nesher cement factory, could take advantage of cheap Arab labour pouring in from the countryside.[14] After 1935 the slump in the construction boom and further concentration by the Yishuv on an exclusivist Hebrew labour programme removed most of the sources of employment for rural migrants.[37] By 1935 only 12,000 Arabs (5% of the workforce) worked in the Jewish sector, half of these in agriculture, whereas 32,000 worked for the Mandate authorities and 211,000 were either self-employed or worked for Arab employers.[38]

The ongoing disruption of agrarian life in Palestine, which had been continuing since Ottoman times, thus created a large population of landless peasant farmers who subsequently became mobile wage workers who were increasingly marginalised and impoverished; these became willing participants in nationalist rebellion.[39] At the same time, Jewish immigration peaked in 1935, just months before Palestinian Arabs began their full-scale, nationwide revolt.[1][40] Over the four years between 1933 and 1936 more than 164,000 Jewish immigrants arrived in Palestine, and between 1931 and 1936 the Jewish population more than doubled from 175,000 to 370,000 people, increasing the Jewish population share from 17% to 27%, and bringing about a significant deterioration in relations between Palestinian Arabs and Jews.[41] In 1936 alone, some 60,000 Jews immigrated that year – the Jewish population having grown under British auspices from 57,000 to 320,000 in 1935[13]

Political and socio-cultural background

The advent of Zionism and British colonial administration crystallised Palestinian nationalism and the desire to defend indigenous traditions and institutions.[42] Palestinian society was largely clan-based (hamula), with an urban land-holding elite lacking a centralised leadership.[42] Traditional feasts such as Nebi Musa began to acquire a political and nationalist dimension and new national memorial days were introduced or gained new significance; among them Balfour Day (2 November), the anniversary of the Battle of Hattin (4 July), and beginning in 1930, 16 May was celebrated as Palestine Day.[43] The expansion of education, the development of civil society and of transportation, communications, and especially of broadcasting and other media, all facilitated notable changes.[44] The Yishuv itself, at the same time, was steadily building the structures for its own state-building with public organisations like the Jewish Agency and the covert creation and consolidation of a paramilitary arm with the Haganah and Irgun.[45]

In 1930 Sheikh Izz ad-Din al-Qassam organised and established the Black Hand, a small anti-Zionist and anti-British militia. He recruited and arranged military training for impoverished but pious peasants but also for ex-criminals he had persuaded to take Islam seriously and they engaged in a campaign of vandalizing tree plantations and British-constructed rail lines,[46] destroying phone lines and disrupting transportation.[47] Three minor mujāhīdūn and jihadist groups had also been formed that advocated armed struggle; these were the Green Hand (al-Kaff al-Khaḍrā) -active in the area of Acre-Safed-Nazareth from 1929 until 1930 when they were dispersed;[48] the Organization for Holy Struggle (al-Jihād al-Muqaddas), led by Abd al-Qadir al-Husayni and operative in the areas of Jerusalem (1931–1934);[48] and the Rebel Youth (al-Shabāb al-Thā'ir), active in the Tulkarm and Qalqilyah area from 1935, and composed mainly of local boy scouts.)[48][43]

The pressures of the 1930s wrought several changes,[42] giving rise to new political organizations and a broader activism that spurred a far wider cross-section of the population in rural areas, strongly nationalist, to join actively in the Palestinian cause.[49] Among new political parties formed in this period were the Independence Party[50] which called for an Indian Congress Party-style boycott of the British,[51] the pro-Nashashibi National Defence Party, the pro-Husayni Palestinian Arab Party the pro-Khalidi Arab-Palestinian Reform Party, and the National Bloc, based mainly around Nablus.[43]

Youth organisations emerged like Young Men's Muslim Association and the Youth Congress Party, the former anti-Zionist, the latter pan-Arab. The Palestinian Boy Scout Movement, founded early in 1936, became active in the general strike.[49] Women's organisations, which had been active in social matters, became politically involved from the end of the 1920s, with an Arab Women's Congress held in Jerusalem in 1929 attracting 200 participants, and an Arab Women's Association (later Arab Women's Union) being established at the same time, both organised by feminist Tarab Abdul Hadi.[49][52] Myriads of rural women would play an important role in response to faz'a alarm calls for inter-village help by rallying in defence of the rebellion.[53]

Inspiration from abroad

General strikes had been used in neighbouring Arab countries to place political pressures on Western colonial powers.[54] In Iraq a general strike in July 1931, accompanied by organised demonstrations in the streets, led to independence for the former British mandate territory under Prime Minister Nuri as-Said, and full membership of the League of Nations in October 1932.[55]The Syrian national movement had used a general strike from 20 January to 6 March in 1936 which, despite harsh reprisals, brought about negotiations in Paris that led to a Franco-Syrian Treaty of Independence.[56] This showed that determined economic and political pressure could challenge a fragile imperial administration.[57]

Prelude

On 16 October 1935 a large arms shipment camouflaged in cement bins, comprising 25 Lewis guns and their bipods, 800 rifles and 400,000 rounds of ammunition[58] destined for the Haganah, was discovered during unloading at the port of Jaffa. The news sparked Arab fears of a Jewish military takeover of Palestine.[59][60] A little over two weeks later, on 2 November 1935, al-Qassam gave a speech in the port of Haifa denouncing the Balfour declaration on its 18th anniversary. In a proclamation to that effect, together with Jamal al-Husayni, he alluded to the Haganah weapons smuggling operation. [61] Questioned at the time by a confidant about his preparations, he stated that he had 15 men, each furnished with a rifle and one cartridge. Soon after, perhaps fearing a pending preemptive arrest, he disappeared with his group into the hills, not to start a revolution, premature at that point, but to impress upon people that he was a man ready to do what he said should be done.[62] Some weeks later, a Jewish policeman was shot dead in a citrus grove while investigating the theft of grapefruit, after he happened to come close to the Qassamites' encampment.[63] Following the incident, the Palestine police launched a massive manhunt and surrounded al-Qassam in a cave just north of Ya'bad. In the ensuing battle, on 20 November, al-Qassam was killed.[64]

The death of al-Qassam generated widespread outrage among Palestinian Arabs, galvanizing public sentiments with an impact similar to the effect on the Yishuv of news of the death of Joseph Trumpeldor in 1920 at the Tel Hai settlement.[65] Huge crowds gathered for the occasion of his obsequies in Haifa and later burial in Balad al-Shaykh.[66]

The actual uprising was triggered some five months later, on 15 April 1936, by the Anabta shooting where remnants of a Qassamite band stopped a convoy on the road from Nablus to Tulkarm, robbed its passengers and, stating that they were acting to revenge al-Qassam's death, shot 3 Jewish passengers, two fatally, after ascertaining their identity.[10] One of the three, Israel Chazan, was from Thessaloniki. The Salonican community's request that permission be granted to allow them to conduct a solemn funeral for Chasan was turned down by the district commissioner, who had allowed al-Qassam a ceremonial burial some months earlier. The refusal sparked a demonstration by 30,000 Jews in Tel Aviv who overcame the police and maltreated Arab labourers and damaged property in Jaffa.[20][67] The following day, two Arab workers sleeping in a hut in a banana plantation beside the highway between Petah Tikva and Yarkona were assassinated in retaliation by members of the Haganah-Bet.[20] [f]

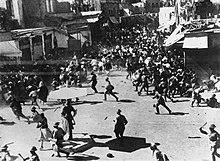

Jews and Palestinians attacked each other in and around Tel Aviv. Palestinians in Jaffa rampaged through a Jewish residential area, resulting in several Jewish deaths.[70] After four days, by 19 April, the deteriorating situation erupted into a set of countrywide disturbances. An Arab general strike and revolt ensued that lasted until October 1936.[1]

Timeline

Arab general strike and armed insurrection, April–October 1936

The strike began on 19 April in Nablus, where an Arab National Committee was formed,[72][73] and by the end of the month National Committees had been formed in all of the towns and some of the larger villages.[73] On the same day, the High Commissioner Wauchope issued Emergency Regulations that laid the legal basis for suppressing the insurgency.[70] On 21 April the leaders of the five main parties accepted the decision at Nablus and called for a general strike of all Arabs engaged in labour, transport and shopkeeping for the following day.[73]

While the strike was initially organised by workers and local committees, under pressure from below, political leaders became involved to help with co-ordination.[74] This led to the formation on 25 April 1936 of the Arab Higher Committee (AHC).[73] The Committee resolved "to continue the general strike until the British Government changes its present policy in a fundamental manner"; the demands were threefold: (1) the prohibition of Jewish immigration; (2) the prohibition of the transfer of Arab land to Jews; (3) the establishment of a National Government responsible to a representative council.[75]

About one month after the general strike started, the leadership group declared a general non-payment of taxes in explicit opposition to Jewish immigration.[76]

In the countryside, armed insurrection started sporadically, becoming more organized over time.[77] One particular target of the rebels was the Mosul–Haifa oil pipeline of the Iraq Petroleum Company constructed only a few years earlier to Haifa from a point on the Jordan River south of Lake Tiberias.[78][79] This was repeatedly bombed at various points along its length. Other attacks were on railways (including trains) and on civilian targets such as Jewish settlements, secluded Jewish neighbourhoods in the mixed cities, and Jews, both individually and in groups.[80] During the summer of that year, thousands of Jewish-farmed acres and orchards were destroyed, Jewish civilians were attacked and murdered, and some Jewish communities, such as those in Beisan and Acre, fled to safer areas.[81]

The measures taken against the strike were harsh from the outset and grew harsher as the revolt deepened. Unable to contain the protests with the two battalions already stationed in the country, Britain inundated Palestine with soldiers from regiments all over the empire, including its Egyptian garrison.[70] The drastic measures taken included house searches without warrants, night raids, preventive detention, caning, flogging, deportation, confiscation of property, and torture.[82] As early as May 1936 the British formed armed Jewish units equipped with armoured vehicles to serve as auxiliary police.[83]

The British government in Palestine was convinced that the strike had the full support of the Palestinian Arabs and they could see "no weakening in the will and spirit of the Arab people."[84] Air Vice-Marshall Richard Peirse, commander of British forces in Palestine and Transjordan from 1933 to 1936, reported that because the rebel armed bands were supported by villagers,

It was quickly evident that the only way to regain the initiative from the rebels was by initiating measures against the villagers from which the rebels and saboteurs came ... I therefore initiated, in co-operation with the Inspector-General of Police R. G. B. Spicer, village searches. Ostensibly, these searches were undertaken to find arms and wanted persons, actually the measures adopted by the Police on the lines of similar Turkish methods, were punitive and effective.[84]

In reality the measures created a sense of solidarity between the villagers and the rebels.[84] The pro-Government Mayor of Nablus complained to the High Commissioner that, "During the last searches effected in villages properties were destroyed, jewels stolen, and the Holy Qur'an torn, and this has increased the excitement of the fellahin."[84] However, Moshe Shertok of the Jewish Agency even suggested that all villages in the area of an incident should be punished.[85]

On 2 June, an attempt by rebels to derail a train bringing the 2nd Battalion Bedfordshire and Hertfordshire Regiment from Egypt led to the railways being put under guard, placing a great strain on the security forces.[86] On 4 June, in response to this situation, the government rounded up a large number of Palestinian leaders and sent them to a detention camp at Auja al-Hafir in the Negev desert.[86]

The Battle of Nur Shams on 21 June marked an escalation with the largest engagement of British troops against Arab militants so far in this Revolt.[87]

During July, Arab volunteers from Syria and Transjordan, led by Fawzi al-Qawukji, helped the rebels to divide their formations into four fronts, each led by a District Commander who had armed platoons of 150–200 fighters, each commanded by a platoon leader.[88]

A Statement of Policy issued by the Colonial Office in London on 7 September declared the situation a "direct challenge to the authority of the British Government in Palestine" and announced the appointment of Lieutenant-General John Dill as supreme military commander.[80] By the end of September 20,000 British troops in Palestine were deployed to "round up Arab bands".[80]

In June 1936 the British involved their clients in Transjordan, Iraq, Saudi Arabia and Egypt in an attempt to pacify the Palestinian Arabs and on 9 October the rulers made an appeal for the strike to be ended.[89] A more pressing concern may have been the approaching citrus harvest and the attractive, soaring prices on the international markets caused by the disruption to the Spanish citrus harvest due to the Spanish Civil War.[90]

On 22 August 1936, Anglo-Jewish Arabist scholar Levi Billig of Hebrew University was murdered in his home outside Jerusalem by an Arab assassin, one of three Jews killed by Arabs on 22 August, and one of 73 Jews killed since the beginning of the Arab armed insurrection.[91][92]

Peel commission; break in hostilities (October 1936 – September 1937)

The strike was called off on 11 October 1936[80] and the violence abated for about a year while the Peel Commission deliberated. The Royal Commission was announced on 18 May 1936 and its members were appointed on 29 July, but the Commission did not arrive in Palestine until 11 November.[93] In the early 1920s the first High Commissioner of Palestine, Herbert Samuel, had failed to create a unified political structure embracing both Palestinian Arabs and Palestinian Jews in constitutional government with joint political institutions.[94] This failure facilitated internal institutional partition in which the Jewish Agency exercised a degree of autonomous control over the Jewish settlement and the Supreme Muslim Council performed a comparable role for Muslims.[94] Thus, well before Lord Peel arrived in Palestine on 11 November 1936, the groundwork for territorial partition as proposed by the Royal Commission in its report on 7 July 1937 had already been done.[94]

The commission, which concluded that 1,000 Arab rebels had been killed during the six month strike, later described the disturbances as "an open rebellion of the Palestinian Arabs, assisted by fellow-Arabs from other countries, against Mandatory rule" and noted two unprecedented features of the revolt: the support of all senior Arab officials in the political and technical departments in the Palestine administration (including all of the Arab judges) and the "interest and sympathy of the neighbouring Arab peoples", which had resulted in support for the rebellion in the form of volunteers from Syria and Iraq.[95]

Peel's main recommendation was for partition of Palestine into a small Jewish state (based on current Jewish land ownership population and incorporating the country's most productive agricultural land), a residual Mandatory area, and a larger Arab state linked to Transjordan.[94] A second and more radical proposal was for transfer of 225,000 Palestinian Arabs from the proposed Jewish state to a future Arab state and Transjordan.[94] It is likely that Zionist leaders played a role in persuading Peel to accept the notion of transfer, which had been a strand of Zionist ideology from its inception.[97]

The Arab Higher Committee rejected the recommendations immediately, as did the Jewish Revisionists. Initially, the religious Zionists, some of the General Zionists, and sections of the Labour Zionist movement also opposed the recommendations.[94] Ben-Gurion was delighted by the Peel Commission's support for transfer, which he viewed as the foundation of "national consolidation in a free homeland."[97] Subsequently, the two main Jewish leaders, Chaim Weizmann and Ben Gurion had convinced the Zionist Congress to approve equivocally the Peel recommendations as a basis for further negotiation,[94][98][g] and to negotiate a modified Peel proposal with the British.[h]

The British government initially accepted the Peel report in principle. However, with war clouds looming over Europe, they realized that to attempt to implement it against the will of the Palestinian Arab majority would rouse up the entire Arab world against Britain.[i] The Woodhead Commission considered three different plans, one of which was based on the Peel plan. Reporting in 1938, the Commission rejected the Peel plan primarily on the grounds that it could not be implemented without a massive forced transfer of Arabs (an option that the British government had already ruled out).[102] With dissent from some of its members, the Commission instead recommended a plan that would leave the Galilee under British mandate, but emphasised serious problems with it that included a lack of financial self-sufficiency of the proposed Arab State.[102] The British Government accompanied the publication of the Woodhead Report by a statement of policy rejecting partition as impracticable due to "political, administrative and financial difficulties".[103]

Resumed revolt (September 1937 – August 1939)

With the failure of the Peel Commission's proposals the revolt resumed during the autumn of 1937 marked by the assassination on 26 September of Acting District Commissioner of the Galilee Lewis Andrews by Quassemite gunmen in Nazareth.[104] Andrews was widely hated by Palestinians for supporting Jewish settlement in the Galilee, and he openly advised Jews to create their own defense force.[105] On 30 September, regulations were issued allowing the Government to detain political deportees in any part of the British Empire, and authorising the High Commissioner to outlaw associations whose objectives he regarded as contrary to public policy. Haj Amin al-Husseini was removed from the leadership of the Supreme Moslem Council and the General Waqf Committee, the local National Committees and the Arab Higher Committee were disbanded; five Arab leaders were arrested and deported to the Seychelles; and in fear of arrest Jamal el-Husseini fled to Syria and Haj Amin el-Husseini to Lebanon;[106][107] all frontiers with Palestine were closed, telephone connections to neighbouring countries were withdrawn, press censorship was introduced and a special concentration camp was opened near Acre.[107]

In November 1937, the Irgun formally rejected the policy of Havlagah and embarked on a series of indiscriminate attacks against Arab civilians as a form of what the group called "active defense" against Arab attacks on Jewish civilians. The British authorities set up military courts, which were established for the trial of offenses connected with the carrying and discharge of firearms, sabotage and intimidation. Despite this, however, the Arab campaign of murder and sabotage continued and Arab gangs in the hills took on the appearance of organised guerrilla fighters.[106] Violence continued throughout 1938.[1] In July 1938, when the Palestine Government seemed to have largely lost control of the situation, the garrison was strengthened from Egypt, and in September it was further reinforced from England. The police were placed under the operational control of the army commander, and military officials superseded the civil authorities in the enforcement of order. In October the Old City of Jerusalem, which had become a rebel stronghold, was reoccupied by the troops. By the end of the year a semblance of order had been restored in the towns, but terrorism continued in rural areas until the outbreak of the Second World War.[106]

Attacks and casualties in numbers

In the final fifteen months of the revolt alone there were 936 murders and 351 attempted murders; 2,125 incidents of sniping; 472 bombs thrown and detonated; 364 cases of armed robbery; 1,453 cases of sabotage against government and commercial property; 323 people abducted; 72 cases of intimidation; 236 Jews killed by Arabs and 435 Arabs killed by Jews; 1,200 rebels killed by the police and military and 535 wounded.[108]

Irgun anti-British attacks

Despite cooperation of the Yishuv with the British to quell the revolt, some incidents towards the end of the conflict indicated a coming change in relations. On 12 June 1939, A British explosives expert was killed trying to defuse an Irgun bomb near a Jerusalem post office. On 26 August, two British police officers, Inspector Ronald Barker and Inspector Ralph Cairns, commander of the Jewish Department of the C.I.D., were killed by an Irgun mine in Jerusalem.[109][110]

Response

Role of the Mandate Government and the British Army

Military law allowed swift prison sentences to be passed.[111] Thousands of Arabs were held in administrative detention, without trial, and without proper sanitation, in overcrowded prison camps.[111]

The British had already formalised the principle of collective punishment in Palestine in the 1924–1925 Collective Responsibility and Punishment Ordinances and updated these ordinances in 1936 with the Collective Fines Ordinance.[1] These collective fines (amounting to £1,000,000 over the revolt[112]) eventually became a heavy burden for poor Palestinian villagers, especially when the army also confiscated livestock, destroyed properties, imposed long curfews and established police posts, demolished houses and detained some or all of the Arab men in distant detention camps.[1]

Full martial law was not introduced but in a series of Orders in Council and Emergency Regulations, 1936–37 'statutory' martial law, a stage between semi-military rule under civil powers and full martial law under military powers, and one in which the army and not the civil High Commissioner was pre-eminent was put in place.[1][113] Following the Arab capture of the Old City of Jerusalem in October 1938, the army effectively took over Jerusalem and then all of Palestine.[1]

The main form of collective punishment employed by the British forces was destruction of property. Sometimes entire villages were reduced to rubble, as happened to Mi'ar in October 1938; more often several prominent houses were blown up and others were trashed inside.[1][85] The biggest single act of destruction occurred in Jaffa on 16 June 1936, when large gelignite charges were used to cut long pathways through the old city, destroying 220–240 buildings and rendering up to 6,000 Arabs homeless.[1] Scathing criticism for this action from Palestine Chief Justice Sir Michael McDonnell was not well received by the administration and the judge was soon removed from the country.[114] Villages were also frequently punished by fines and confiscation of livestock.[1] The British even used sea mines from the battleship HMS Malaya to destroy houses.[1]

In addition to actions against property, a large amount of brutality by the British forces occurred, including beatings, torture and extrajudicial killings.[1] A surprisingly large number of prisoners were "shot while trying to escape".[1] Several incidents involved serious atrocities, such as massacres at al-Bassa and Halhul.[1] Desmond Woods, an officer of the Royal Ulster Rifles, described the massacre at al-Bassa:

Now I will never forget this incident ... We were at al-Malikiyya, the other frontier base and word came through about 6 o'clock in the morning that one of our patrols had been blown up and Millie Law [the dead officer] had been killed. Now Gerald Whitfeld [Lieutenant-Colonel G.H.P. Whitfeld, the battalion commander] had told these mukhtars that if any of this sort of thing happened he would take punitive measures against the nearest village to the scene of the mine. Well the nearest village to the scene of the mine was a place called al-Bassa and our Company C were ordered to take part in punitive measures. And I will never forget arriving at al-Bassa and seeing the Rolls-Royce armoured cars of the 11th Hussars peppering Bassa with machine gun fire and this went on for about 20 minutes and then we went in and I remembered we had lighted braziers and we set the houses on fire and we burnt the village to the ground ... Monty had him [the battalion commander] up and he asked him all about it and Gerald Whitfeld explained to him. He said "Sir, I have warned the mukhtars in these villages that if this happened to any of my officers or men, I would take punitive measures against them and I did this and I would've lost control of the frontier if I hadn't." Monty said "All right but just go a wee bit easier in the future."[1]

As well as destroying the village the RUR and men from the Royal Engineers collected around fifty men from al-Bassa and blew some of them up with explosion under a bus. Harry Arrigonie, a policeman who was present said that about twenty men were put onto a bus; those who tried to escape were shot and then the driver of the bus was forced to drive over a powerful land mine buried by the soldiers which completely destroyed the bus, scattering the mutilated bodies of the prisoners everywhere. The other villagers were then forced to bury the bodies in a pit.[1]

Despite these measures Lieutenant-General Haining, the General Officer Commanding, reported secretly to the Cabinet on 1 December 1938 that "practically every village in the country harbours and supports the rebels and will assist in concealing their identity from the Government Forces."[115] Haining reported the method for searching villages:

A cordon round the area to be searched is first established either by troops or aircraft and the inhabitants are warned that anybody trying to break through the cordon is likely to be shot. As literally hundreds of villages have been searched, in some cases more than once, during the past six months this procedure is well-known and it can be safely assumed that cordon-breakers have good reasons for wishing to avoid the troops. A number of such cordon-breakers have been shot during searches and it is probable that such cases form the basis of the propaganda that Arab prisoners are shot in cold blood and reported as "killed while trying to escape". After the cordon is established the troops enter the village and all male inhabitants are collected for identification and interrogation.[115]

The report was issued in response to growing concern at the severity of the military measures amongst the general public in Great Britain, among members of the British Government, and among governments in countries neighbouring Palestine.[115]

In addition to actions against villages the British Army also conducted punitive actions in the cities. In Nablus in August 1938 almost 5,000 men were held in a cage for two days and interrogated one after another.[116] During their detention the city was searched and then each of the detainees was marked with a rubber stamp on his release.[116] At one point a night curfew was imposed on most of the cities.[116]

It was common British army practice to use local Arabs as human shields by forcing them to ride with military convoys to prevent mine attacks and sniping incidents: soldiers would tie the hostages to the bonnets of lorries, or put them on small flatbeds on the front of trains.[1] The army told the hostages that any of them who tried to run away would be shot. On the lorries, some soldiers would brake hard at the end of a journey and then casually drive over the hostage, killing or maiming him, as Arthur Lane, a Manchester Regiment private recalled:

... when you'd finished your duty you would come away nothing had happened no bombs or anything and the driver would switch his wheel back and to make the truck waver and the poor wog on the front would roll off into the deck. Well if he was lucky he'd get away with a broken leg but if he was unlucky the truck behind coming up behind would hit him. But nobody bothered to pick up the bits they were left. You know we were there we were the masters we were the bosses and whatever we did was right ... Well you know you don't want him any more. He's fulfilled his job. And that's when Bill Usher [the commanding officer] said that it had to stop because before long they'd be running out of bloody rebels to sit on the bonnet.[1]

British troops also left Arab wounded on the battlefield to die and maltreated Arab fighters taken in battle, so much so that the rebels tried to remove their wounded or dead from the field of battle.[1] Sometimes, soldiers would occupy villages, expel all of the inhabitants and remain for months.[117] The Army even burned the bodies of "terrorists" to prevent their funerals becoming the focus of protests.[117]

Tegart forts

Sir Charles Tegart was a senior police officer brought into Palestine from the colonial force of British India[1] on 21 October 1937.[118] Tegart and his deputy David Petrie (later head of MI5) advised a greater emphasis on foreign intelligence gathering and closure of Palestine's borders.[119] Like many of those enrolled in the Palestinian gendarmerie, Tegart had served in Great Britain's repression of the Irish War of Independence, and the security proposals he introduced exceeded measures adopted down to this time elsewhere in the British Empire. 70 fortresses were erected throughout the country at strategic choke points and near Palestinian villages which, if assessed as "bad", were subjected to collective punishment.[120][121] Accordingly, from 1938 Gilbert Mackereth, the British Consul in Damascus, corresponded with Syrian and Transjordan authorities regarding border control and security to counteract arms smuggling and "terrorist" infiltration and produced a report for Tegart on the activities of the Palestine Defence Committee in Damascus.[122] Tegart recommended the construction of a frontier road with a barbed wire fence, which became known as Tegart's wall, along the borders with Lebanon and Syria to help prevent the flow of insurgents, goods and weapons.[118] Tegart encouraged close co-operation with the Jewish Agency.[123] It was built by the Histadrut construction company Solel Boneh.[123] The total cost was £2 million.[123] The Army forced the fellahin to work on the roads without pay.[124]

Tegart introduced Arab Investigation Centres where prisoners were subjected to beatings, foot whipping, electric shocks, denailing and what is now known as "waterboarding".[1] Tegart also imported Doberman Pinschers from South Africa and set up a special centre in Jerusalem to train interrogators in torture.[125]

Role of the Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force developed close air support into its then most refined form during the Arab Revolt.[126] Air patrols had been found effective in keeping convoys and trains free from attack, but this did not help to expose insurgents to battle conditions likely to cause their defeat.[126] From the middle of June 1936 wireless vehicles accompanied all convoys and patrols.[126] During rebel attacks these vehicles could issue emergency "XX calls" (XX with a coded location), which were given priority over all other radio traffic, to summon aerial reinforcements.[126] Bombers, which were usually airborne within five minutes, could then either attack insurgents directly or "fix" their position for infantry troops. Forty-seven such XX calls were issued during the revolt, causing heavy losses to the rebels.[126] In the June 1936 Battle of Nur Shams British planes attacked Arab irregulars with machine gun fire.

This use of air power was so successful that the British were able to reduce the regular garrison.[126]

In 1936 an Air Staff Officer in Middle East Command based in the Kingdom of Egypt, Arthur Harris, known as an advocate of "air policing",[127] commented on the revolt saying that "one 250 lb. or 500 lb. bomb in each village that speaks out of turn" would satisfactorily solve the problem.[128] In 1937 Harris was promoted to Air Commodore and in 1938 he was posted to Palestine and Trans-Jordan as Air Officer Commanding the RAF contingent in the region until September 1939. "Limited" bombing attacks on Arab villages were carried out by the RAF,[129] although at times this involved razing whole villages.[130] Harris described the system by which recalcitrant villages were kept under control by aerial bombardment as "Air-Pin".[131]

Aircraft of the RAF were also used to drop propaganda leaflets over Palestinian towns and villages telling the fellahin that they were the main sufferers of the rebellion and threatening an increase in taxes.[124]

Low flying RAF squadrons were able to produce detailed intelligence on the location of road blocks, sabotaged bridges, railways and pipelines.[132] RAF aerial photographs were also used to build up a detailed map of Arab population distribution.[132]

Although the British Army was responsible for setting up the Arab counter-insurgent forces (known as the peace bands) and supplying them with arms and money these were operated by RAF Intelligence, commanded by Patrick Domville.[133][134]

At the beginning of the revolt RAF assets in the region comprised a bomber flight at RAF Ramleh, an RAF armoured car flight at Ramleh, fourteen bomber squadrons at RAF Amman, and a RAF armoured car company at Ma'an.[5]

Role of the Royal Navy

At the beginning of the Revolt crew from the Haifa Naval Force's two cruisers were used to carry out tasks ashore, manning two howitzers and naval lorries equipped with QF 2 pounder naval guns and searchlights used to disperse Arab snipers.[135] From the end of June two destroyers were used to patrol the coast of Palestine in a bid to prevent gun running.[135] These searched as many as 150 vessels per week and were an effective preventive measure.[135] At the request of the Army additional naval platoons landed in July to help protect Haifa and Jewish settlements in the surrounding countryside.[135] The Navy also relieved the Army of duties in Haifa by using nine naval platoons to form the Haifa Town Force and in August three naval platoons were landed to support the police.[135]

Following publication of the Peel Commission's report in July 1937 HMS Repulse sailed to Haifa where landing parties were put ashore to maintain calm.[135] Various other naval vessels continued with this role until the end of the revolt.[135]

Following the Irgun's detonation of a large bomb in a market in Haifa on 6 July 1938 the High Commissioner signalled the Commander-in-Chief of the Mediterranean Fleet, Admiral Sir Dudley Pound, requesting the assistance of naval vessels capable of providing landing parties.[135] Pound dispatched HMS Repulse and diverted HMS Emerald to Haifa, which arrived the same day and landed five platoons, one to each police district.[135] HMS Repulse relieved HMS Emerald the following day and after another bomb was detonated on 10 July five platoons from the ship, made up of sailors and Royal Marines, dispersed mobs and patrolled the city.[135]

On 11 July provision of three platoons from Repulse released men of the West Kent Regiment for a punitive mission against Arabs who had attacked a Jewish colony near Haifa.[135] By 17 July the Repulse established a Company Headquarters where seamen and Royal Marines manned a 3.7-inch howitzer.[135] Sailors, Royal Marines, and men of the Suffolk Regiment, who had embarked on the Repulse, accompanied foot patrols of the Palestine Police Force.[135]

The Repulse, HMS Hood and HMS Warspite provided howitzer crews which were sent ashore to combat gun running near the border with Lebanon.[135] Detained Arabs were used to build emplacements and the howitzers were moved quickly between these positions by day and night to confuse bandits as to the likely direction of fire.[135] Periodically, the guns were used to fire warning rounds close to the vicinity of villages believed to have rebel sympathies.[135]

Strategic importance of Haifa

Britain had completed the modern deep-sea port in Haifa in 1933 and finished laying a pipeline from the Iraqi oilfields to Haifa in 1935,[136] shortly before the outbreak of the revolt. A refinery for processing oil from the pipeline was completed by Consolidated Refineries Ltd, a company jointly owned by British Petroleum and Royal Dutch Shell, in December 1939.[137]

These facilities enhanced the strategic importance of Palestine and of Haifa in particular in Britain's control of the eastern Mediterranean.[136] The threat to British control of the region posed by the Italian invasion of Abyssinia in October 1935 and the deteriorating situation in Europe toward the end of the 1930s probably made British policy makers more willing to make concessions to Arab governments on the Palestine issue following the furore over the recommendations of the Peel Commission.[136]

Role of the British intelligence services

The Arab Revolt was the last major test of Britain's security services in the Middle East before World War II.[138] The development and deployment of intelligence-led counterinsurgency strategies was integral to the restoration of British imperial control in Palestine as the revolt had demonstrated to the British authorities how a popular rebellion could undermine intelligence gathering operations and thereby impair their ability to predict and respond to inter-communal disorder.[138] The rebellion had brought together urban nationalism and peasant economic grievances arising from rural poverty and landlessness, which was blamed on British misrule.[138] Accordingly, the Palestinian revolt targeted the political and economic apparatus of the British colonial state, including the communications network, pipelines, police stations, army outposts and British personnel.[138] It was this aspect of the revolt, rather than attacks on Jews or violence between rivals for leadership of the national movement, that most concerned the high commissioner.[138] The mandate authorities were further disturbed by the unity of purpose displayed during the six-month general strike and by the resurgence of pan-Arab nationalism as evidenced by the rise of the Istiqlal Party.[138]

In response to these challenges the British army command ("I" Branch) and battalion headquarters across Palestine issued a daily intelligence bulletin every afternoon detailing political developments.[138] Special Service Officers (SSOs) assigned to intelligence gathering reported directly to their local command headquarters and their cars were equipped with wireless transmitters so that high grade intelligence could be reported directly to "I" Branch immediately.[138] These sources of intelligence gradually became more important than those of the C.I.D. in Palestine, which had been dependent on Arab informers, and which were no longer reliable.[138]

In September 1937, the Jewish Agency appointed Reuven Zaslany liaison officer for intelligence and security affairs between the Political Department of the Jewish Agency and the intelligence arms of the Royal Air Force and the C.I.D.[139] Zaslany sifted through intelligence collected by Jewish-controlled field operatives and forwarded it to the British military.[139] He was a frequent visitor at the headquarters of British intelligence and the army, the police and C.I.D. and he also travelled to Damascus to liaise with the Arab opposition's peace bands and with the British Consul in Iraq.[139] Colonel Frederick Kisch, a British army officer and Zionist leader, was appointed chief liaison officer between the British army and the Jewish Agency Executive with Zaslany as his deputy.[139] Zaslany also worked as interpreter for Patrick Domville, head of RAF Intelligence in Palestine (who was described by Haganah leader Dov Hos as the "best Zionist informer on the English"), until the latter was posted to Iraq in 1938, and through him became acquainted with many of the British intelligence officers.[140]

In 1937 the Jewish Agency's intelligence groups were responsible for bugging the Peel Commission hearings in Palestine.[141] Eventually, the Arab Revolt convinced the Agency that a central intelligence service was required and this led to the formation of a counter-intelligence agency known as the Ran (headed by Yehuda Arazi, who also helped to smuggle rifles, machine guns and ammunition from Poland to Palestine) and thereafter in 1940 to the creation of SHAI, the forerunner of Mossad.[142][143]

British and Jewish co-operation

The Haganah (Hebrew for "defence"), a Jewish paramilitary organisation, actively supported British efforts to suppress the uprising, which reached 10,000 Arab fighters at their peak during the summer and fall of 1938. Although the British administration did not officially recognise the Haganah, the British security forces cooperated with it by forming the Jewish Settlement Police, Jewish Supernumerary Police, and Special Night Squads. The Special Night Squads engaged in activities described by colonial administrator Sir Hugh Foot, as 'extreme and cruel' involving torture, whipping, abuse and execution of Arabs.[1]

The British authorities maintained, financed and armed the Jewish police from this point onward until the end of the Mandate,[144] and by the end of September 1939 around 20,000 Jewish policeman, supernumeraries and settlement guards had been authorised to carry arms by the government,[3] which also distributed weapons to outlying Jewish settlements,[145]and allowed the Haganah to acquire arms.[146] Independently of the British, Ta'as, the Haganah's clandestine munitions industry, developed an 81-mm mortar and manufactured mines and grenades, 17,500 of the latter being produced for use during the revolt.[29][147][148]

In June 1937, the British imposed the death penalty for unauthorised possession of weapons, ammunition, and explosives, but since many Jews had permission to carry weapons and store ammunition for defence this order was directed primarily against Palestinian Arabs and most of the 108 executed in Acre Prison were hanged for illegal possession of arms.[149]

In principle all of the joint units functioned as part of the British administration, but in practice they were under the command of the Jewish Agency and "intended to form the backbone of a Jewish military force set up under British sponsorship in preparation for the inevitable clash with the Arabs."[150] The Agency and the Mandate authorities shared the costs of the new units equally.[123] The administration also provided security services to Jewish commercial concerns at cost.[123]

Jewish and British officials worked together to co-ordinate manhunts and collective actions against villages and also discussed the imposition of penalties and sentences.[150] Overall, the Jewish Agency was successful in making "the point that the Zionist movement and the British Empire were standing shoulder to shoulder against a common enemy, in a war in which they had common goals."[151]

The rebellion also inspired the Jewish Agency to expand the intelligence-gathering of its Political Department and especially of its Arab Division, with the focus changing from political to military intelligence.[152] The Arab Division set up a network of Jewish controllers and Arab agents around the country.[152] Some of the intelligence gathered was shared with the British administration, the exchange of information sometimes being conducted by Moshe Shertok, then head of the Jewish Agency, directly with the high commissioner himself.[150] Shertok also advised the administration on political affairs, on one occasion convincing the high commissioner not to arrest Professor Joseph Klausner, a Revisionist Maximalist activist who had played a key role in the riots of 1929, because of the likely negative consequences.[150]

Forces of the Jewish settlement

Table 1: Security forces and infrastructure created during the Arab revolt Joint British-Yishuv Independent Yishuv Other Yishuv defence infrastructure Jewish Supernumerary Police Mobile units (mobile arm of the Haganah) Ta'as † (weapons manufacture) Jewish Settlement Police Fosh (field companies) Rekhesh † (arms procurement) Mobile Guards (mobile arm of the Settlement Police) Hish (field corps) Ran (counter intelligence) Special Night Squads Special Operations Squads Community ransom (defence tax) Tegart forts and Tegart's wall Guards Tower and stockade settlement

† Ta'as and Rekhesh were developed and expanded during the Arab Revolt but already existed before 1936 and the Haganah had been in operation from the earliest days of the Mandate.

Haganah intelligence services

There was no single body within the Jewish settlement capable of co-ordinating intelligence gathering before 1939.[153] Until then there were four separate organisations without any regular or formal liaison.[153] These were an underground militia, forerunner of the first official information service, Sherut Yediot (Shai); the Arab Platoon of the Palmach, which was staffed by Jews who were Arab-speaking and Arab-looking; Rekhesh, the arms procurement service, which had its own intelligence gathering capabilities, and likewise the Mossad LeAliyah Bet, the illegal immigration service.[153] In mid-1939 the effort to co-ordinate the activities of these groups was led by Shaul Avigur and Moshe Shertok.[153]

Role of the Revisionist Zionists

In 1931, a Revisionist underground splinter group broke off from Haganah, calling itself the Irgun organisation (or Etzel).[154] The organisation took its orders from Revisionist leader Ze'ev Jabotinsky who was at odds with the dominant Labour Zionist movement led by David Ben-Gurion.[155] The rift between the two Zionist movements further deteriorated in 1933 when two Revisionists were blamed for the murder of Haim Arlosoroff, who had negotiated the Haavara Agreement between the Jewish Agency and Nazi Germany.[155] The agreement brought 52,000 German Jews to Palestine between 1933 and 1939, and generated $30,000,000 for the then almost bankrupt Jewish Agency, but in addition to the difficulties with the Revisionists, who advocated a boycott of Germany, it caused the Yishuv to be isolated from the rest of world Jewry.[156][157][158]

Ultimately, however, the events of the Arab Revolt blurred the differences between the gradualist approach of Ben-Gurion and the Maximalist Iron Wall approach of Jabotinsky and turned militarist patriotism into a bipartisan philosophy.[159] Indeed, Ben-Gurion's own Special Operations Squads conducted a punitive operation in the Arab village of Lubya firing weapons into a room through a window killing two men and one woman and injuring three people, including two children.[160]

From October 1937 the Irgun instituted a wave of bombings against Arab crowds and buses.[161] For the first time in the conflict massive bombs were placed in crowded Arab public places, killing and maiming dozens.[161] These attacks substantially increased Arab casualties and sowed terror among the population.[161] The first attack was on 11 November 1937, killing two Arabs at the bus depot near Jaffa Street in Jerusalem and then on 14 November, a day later commemorated as the "Day of the Breaking of the Havlagah (restraint)," Arabs were killed in simultaneous attacks around Palestine.[161] More deadly attacks followed: on 6 July 1938 21 Arabs were killed and 52 wounded by a bomb in a Haifa market; on 25 July a second market bomb in Haifa killed at least 39 Arabs and injured 70; a bomb in Jaffa's vegetable market on 26 August killed 24 Arabs and wounded 39.[161] The attacks were condemned by the Jewish Agency.[161]

Role of the "peace bands"

The "peace bands" (fasa'il al-salam) or "Nashashibi units" were made up of disaffected Arab peasants recruited by the British administration and the Nashashibis in late 1938 to battle against Arab rebels during the revolt.[83][162] Despite their peasant origins the bands were representative mainly of the interests of landlords and rural notables.[162] Some peace bands also sprang up in the Nablus area, on Mount Carmel (a stronghold of the Druze who largely opposed the rebellion after 1937), and around Nazareth without connection to the Nashashibi-Husayni power struggle.[163]

From December 1937 the main opposition figures among the Arabs approached the Jewish Agency for funding and assistance,[164] motivated by the assassination campaign pursued by the rebels at the behest of the Husseini leadership.[j] In October 1937, shortly after Mohammad Amin al-Husayni, the leader of the Arab Higher Committee, had fled from Palestine to escape British retribution, Raghib al-Nashashibi had written to Moshe Shertok stating his full willingness to co-operate with the Jewish Agency and to agree with whatever policy it proposed.[104] From early in 1938 the Nashashibis received funding specifically to conduct anti-rebel operations, with Raghib al-Nashashibi himself receiving £5,000.[166] The British also supplied funding to the peace bands and sometimes directed their operations.[166]

Fakhri Nashashibi was particularly successful in recruiting peace bands in the Hebron hills, on one occasion in December 1938 gathering 3,000 villagers for a rally in Yatta, also attended by the British military commander of the Jerusalem District General Richard O'Connor.[166] Just two months earlier, on 15 October 1938, rebels had seized the Old City and barricaded the gates.[167] O'Connor had planned the operation by which men of the Coldstream Guards, Royal Northumberland Fusiliers and Black Watch recaptured the Old City, killing 19 rebels.[166]

Towards the end of the revolt in May 1939 the authorities dissolved the peace bands and confiscated their arms.[166] However, because members of the bands had become tainted in the eyes of the Palestinian Arabs, and some were under sentence of death, they had little choice but to continue the battle against the national movement's leadership, which they did with the continuing help of the Zionist movement.[168]

Role of rebel leaders

At least 282 rebel leaders took part in the Arab Revolt, including four Christians.[169] Rebel forces consisted of loosely organized bands known as fasa'il [170] (sing: fasil).[171] The leader of a fasil was known as a qa'id al-fasil (pl. quwwa'id al-fasa'il), which means "band commander".[172] The Jewish press often referred to them as "brigands", while the British authorities and media called them "bandits", "terrorists", "rebels" or "insurgents", but never "nationalists".[173] Ursabat (meaning "gangs") was another Arabic term used for the rebels,[174] and it spawned the British soldiers' nickname for all rebels, which was Oozlebart.[173][174][175]

According to historian Simon Anglim, the rebel groups were divided into general categories: mujahadeen and fedayeen. The former were guerrillas who engaged in armed confrontations, while the latter committed acts of sabotage.[174] According to later accounts of some surviving rebel leaders from the Galilee, the mujahideen maintained little coordination with the nominal hierarchy of the revolt. Most ambushes were the result of a local initiative undertaken by a qa'id or a group of quwwa'id from the same area.[171]

Galilee

Abdul Khallik was an effective peasant leader appointed by Fawzi al-Qawuqji who caused great damage and loss of life in the Nazareth District and was thus a significant adversary of the Mandate and Jewish settlement authorities.[176] He was trapped by British troops in a major engagement on 2 October 1938 and was killed whilst trying to lead his men to safety.[176][177] Abu Ibrahim al-Kabir was the main Qassamite rebel leader in the Upper Galilee and was the only active rebel leader on the ground who was a member of the Damascus-based Central Committee of National Jihad.[178] Abdallah al-Asbah was a prominent commander active in the Safad region of northeastern Galilee. He was killed by British forces who besieged him and his comrades near the border with Lebanon in early 1937.[179]

Jabal Nablus area

Abd al-Rahim al-Hajj Muhammad from the Tulkarm area was a deeply religious, intellectual man and as a fervent anti-Zionist, he was deeply committed to the revolt.[180] He was regarded second to Qawukji in terms of leadership ability and maintained his independence from the exiled rebel leadership in Damascus.[180] [181] He personally led his fasa'il and carried out nighttime attacks against British targets in the revolt's early stage in 1936. When the revolt was renewed in April 1937, he established a more organised command hierarchy consisting of four main brigades who operated in the north-central highlands (Tulkarm-Nablus-Jenin area). He competed for the position of General Commander of the Revolt with Aref Abdul Razzik, and the two served the post in rotation from September 1938 to February 1939, when al-Hajj Muhammad was confirmed as the sole General Commander.

Al-Hajj Muhammad refused to carry out political assassinations at the behest of political factions, including al-Husayni, once stating "I don't work for Husayniya ('Husanyni-ism'), but for wataniya ('nationalism')."[182] He is still known by Palestinians as a hero and martyr and is regarded as a metonym "for a national movement that was popular, honourable, religious, and lofty in its aims and actions."[183] He was shot dead in a firefight with British forces outside the village of Sanur on 27 March 1939, after Farid Irsheid's peace band informed the authorities of his location.[180]

Yusuf Abu Durra, a Qassamite leader in the Jenin area, was born in Silat al-Harithiya and before becoming a rebel worked as a Gazoz vendor.[184] He was said to be a narrow-minded man who thrived on extortion and cruelty and thus became greatly feared.[184] Yusuf Hamdan was Durra's more respected lieutenant and later a leader of his own unit; he was killed by an army patrol in 1939 and buried in al-Lajjun.[184] Durra himself was apprehended by the Arab Legion in Transjordan on 25 July 1939 and subsequently hanged.[184]

Fakhri Abdul Hadi of Arrabah worked closely with Fawzi al-Qawukji in 1936, but later defected to the British authorities.[176] He bargained for a pardon by offering to collaborate with the British on countering rebel propaganda.[176] Once on the payroll of the British consul in Damascus, Gilbert Mackereth, he carried out many attacks against the rebels in 1938–1939 as leader of his own "peace band".[185][186]

Aref had a little mare

Its coat as white as snow

And where that mare and Aref went

We're jiggered if we know. – British Army verse.

Aref Abdul Razzik of Tayibe was responsible for the area south of Tulkarm and was known for evading capture whilst being pursued by the security forces.[187] He signed his bulletins as 'The Ghost of Sheikh Qassam'.[187] Razzik assumed a place in British army folklore and the troops sang a song about him.[187] Razzik was capable and daring and gained a reputation as one of the army's problem heroes.[187]

Jerusalem area

Issa Battat was a peasant leader in the southern hills below Jerusalem who caused enormous damage to security patrols in his area.[188] He was killed by a patrol of armed police in a battle near Hebron in 1937.[188][189]

Arab volunteers

In the first phase of the revolt, around 300 volunteers, mostly veterans of the Ottoman Army and/or rebels from the Great Syrian Revolt (1925–27), deployed in northern Palestine. Their overall commander was Fawzi al-Qawuqji and his deputies were Said al-As and Muhammad al-Ashmar. Qawuqji also led the volunteer force's Iraqi and Transjordanian battalions, and al-Ashmar was commander of the Syrian battalion, which largely consisted of volunteers from Damascus's al-Midan Quarter, Hama and Homs. The Druze ex-Ottoman officer, Hamad Sa'ab, commanded the Lebanese battalion.[citation needed]

Funding

In the contest of wills between the British Empire and Palestinian aspirants for statehood, the respective efforts to secure the financial means to sustain the hostilities also played out as a battle for funding.[k] The Mandatory Authority's repression of the revolt was bankrolled directly from London and through the revenue stream supplied to the administration by land and property taxes, stamp duties, excises on manufactured goods and customs duties on imports and exports. Draconian collective punishment fines on the peasantry –many heavily burdened already by debt and unable to pay them – were such that revenue extracted from punitive fines exceeded, and more than compensated for, the revenue lost during the revolt.[190]

The majority of funds raised to finance the uprising came from Arab/Muslim sources. In the broader Arab/Muslim world a measure of financial aid, never vast, filtered in from Egypt, Syria, Iraq and Muslim India for some time.[191] In Palestine, the peasantry, often debt-ridden, could offer little towards subsidising the resistance.[192] A variety of measures were adopted. Women donated jewelry and ran fund-raising committees, a jihad tax was placed on citrus groves, the industry being the backbone of Palestine's export trade; Palestinians on the government payroll contributed sums anywhere up to half of their salaries; levies were imposed on wealthier Arabs (many of whom went abroad to avoid paying them, or because they could not meet demands to provide financial aid to strikers).[193] The AHC's functions in this capacity were truncated when it was abolished by the British authorities in October 1937. Displaced in Damascus, its leaders were cut off from contact with field units and donations gradually dried up.[194] al-Husayni, by then in exile, proved unable to raise money, and in Syria militant contacts were informed by July 1938 that they would have to make do on their own.[195] By 1938 the drop in revenues caused militant gangs to resort to extortion and robbery, often draining villages of ready cash reserves set aside to pay government fines, which then had to be met by the sale of crops and livestock.[196] Some contributions were obtained from American sources.[195]

A great deal of speculation later arose around the purported role of Germany and Italy in backing the revolt financially, based on early claims by Jewish operatives that both countries were fomenting the uprising by funneling cash and weapons to the insurgents.[l] German plans to ship arms to the rebels were never implemented due to distrust of the Saudi middlemen.[199] Italian attempts to furnish arms by the same venue were thwarted by British intelligence.[191] The British never found arms or munitions of German or Italian provenance. RAF intelligence dismissed these claims as either referring to 'comparatively small' sums or as purveyed to bring discredit on the Palestinians.[200] al-Husayni and his associates received limited[201] funding from Fascist Italy during the revolt as the Italians were in dispute with the United Kingdom over Abyssinia and wished not only to disrupt the British rear[202] but also to extend Italian influence in the region.[203] The rebels utilized the Italian funding to smuggle weapons into Palestine via Syria.[204] Total Italian funding amounted to approximately £150.000.[205] It stopped in late 1938[191] and played no decisive role since the uprising peaked after that date.[206]

In the first years after 1933 Germany was approached by a variety of Arab nationalist groups from Palestine and abroad asking for aid, but Germany categorically refused. Maintaining good relations with the British was still considered to be of the uppermost priority, hence it limited itself to expressing its sympathy and moral support.[207] Soon after the outbreak of the revolt, in December 1936, Germany was approached by the rebel commander Fawzi al-Qawuqji and in January 1937 by representatives of the Arab Higher Committee, both requesting arms and money, but again in vain.[208] In July al-Husayni himself approached Heinrich Doehle, new general counsel of Jerusalem, to request support for the "battle against the Jews".[209] Doehle found that Germany's hesitation in supporting the rebels had caused pro-German sentiment among Palestinian Arabs to waver.[210] Some limited[m] German funding for the revolt can be dated to around the summer of 1938[199] and was perhaps related to a goal of distracting the British from the on-going occupation of Czechoslovakia.[212] The Abwehr gave money to al-Husayni[199] and other sums were funneled via Saudi Arabia.[213]

Outcome

Casualties

Despite the intervention of up to 50,000 British troops and 15,000 Haganah men, the uprising continued for over three years. By the time it concluded in September 1939, more than 5,000 Arabs, over 300 Jews, and 262 Britons had been killed and at least 15,000 Arabs were wounded.[1]

Impact on the Jewish Yishuv

In the overall context of the Jewish settlement's development in the 1930s the physical losses endured during the revolt were relatively insignificant.[29] Although hundreds were killed and property was damaged no Jewish settlement was captured or destroyed and several dozen new ones were established.[29] Over 50,000 new Jewish immigrants arrived in Palestine.[29] In 1936 Jews made up about one-third of the population.[214]

The hostilities contributed to further disengagement of the Jewish and Arab economies in Palestine, which were intertwined to some extent until that time. Development of the economy and infrastructure accelerated.[29] For example, whereas the Jewish city of Tel Aviv relied on the nearby Arab seaport of Jaffa, hostilities dictated the construction of a separate Jewish-run seaport for Tel Aviv,[29] inspiring the delighted Ben-Gurion to note in his diary "we ought to reward the Arabs for giving us the impetus for this great creation."[215] Metal works were established to produce armoured sheeting for vehicles and a rudimentary arms industry was founded.[29] The settlement's transportation capabilities were enhanced and Jewish unemployment was relieved owing to the employment of police officers,[29] and replacement of striking Arab labourers, employees, craftsman and farmers by Jewish workers.[214] Most of the important industries in Palestine were owned by Jews and in trade and the banking sector they were much better placed than the Arabs.[214]

As a result of collaboration with the British colonial authorities and security forces many thousands of young men had their first experience of military training, which Moshe Shertok and Haganah leader Eliyahu Golomb cited as one of the fruits of the Haganah's policy of havlagah (restraint).[216]

Although the Jewish settlement in Palestine was dismayed by the publication of the 1939 White Paper restricting Jewish immigration, David Ben-Gurion remained undeterred, believing that the policy would not be implemented, and in fact Neville Chamberlain had told him that the policy would last at the very most only for the duration of the war.[217] In the event the White Paper quotas were exhausted only in December 1944, over five and a half years later, and in the same period the United Kingdom absorbed 50,000 Jewish refugees and the British Commonwealth (Australia, Canada and South Africa) took many thousands more.[218] During the War over 30,000 Jews joined the British forces and even the Irgun ceased operations against the British until 1944.[219]

Impact on the Palestinian Arabs

The revolt weakened the military strength of Palestinian Arabs in advance of their ultimate confrontation with the Jewish settlement in the 1947–48 Civil War in Mandatory Palestine and was, according to Benny Morris, thus counterproductive.[220] During the uprising, British authorities attempted to confiscate all weapons from the Arab population. This, and the destruction of the main Arab political leadership in the revolt, greatly hindered their military efforts in the 1948 Palestine war,[30] where imbalances between the Jewish and Arab economic performance, social cohesion, political organisation and military capability became apparent.[214]

The Mufti, Hajj Amin al-Husseini and his supporters directed a Jihad against any person who did not obey the Mufti. Their national struggle was a religious holy war, and the incarnation of both the Palestinian Arab nation and Islam was Hajj Amin al-Husseini. Anyone who rejected his leadership was a heretic and his life was forfeit.[n] After the Peel report publication, the murders of Arabs leaders who opposed the Mufti were accelerated.[222] Pressed by the assassination campaign pursued by the rebels at the behest of the Husseini leadership, the opposition had a security cooperation with the Jews.[165] The flight of wealthy Arabs, which occurred during the revolt, was also replicated in 1947–49.[83]

Thousands of Palestinian houses were destroyed, and massive financial costs were incurred because of the general strike and the devastation of fields, crops and orchards. The economic boycott further damaged the fragile Palestinian Arab economy through loss of sales and goods and increased unemployment.[223] The revolt did not achieve its goals, although it is "credited with signifying the birth of the Arab Palestinian identity."[224] It is generally credited with forcing the issuance of the White Paper of 1939 in which Britain retreated from the partition arrangements proposed by the Peel Commission in favour of the creation of a binational state within ten years, although The League of Nations commission held that the White Paper was in conflict with the terms of the Mandate as put forth in the past.[106][o] The White Paper of 1939 was regarded by many as incompatible with the commitment to a Jewish National Home in Palestine, as proclaimed in the 1917 Balfour Declaration. Al-Husseini rejected the new policy, although it seems that the ordinary Palestinian Arab accepted the White Paper of 1939. His biographer, Philip Mattar wrote that in that case, the Mufti preferred his personal interests and the ideology rather than the practical considerations.[30]

Impact on the British Empire

As the inevitable war with Germany approached, British policy makers concluded that although they could rely on the support of the Jewish population in Palestine, who had no alternative but to support Britain, the support of Arab governments and populations in an area of great strategic importance for the British Empire was not assured.[225] Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain concluded "if we must offend one side, let us offend the Jews rather than the Arabs."[225]

In February 1939 Secretary of State for Dominion Affairs Malcolm MacDonald called together a conference of Arab and Zionist leaders on the future of Palestine at St. James's Palace in London but the discussions ended without agreement on 27 March.[136]The government's new policy as published in White Paper of 17 May had been determined already and despite Jewish protests and Irgun attacks the British remained resolute.[226]

There was a growing feeling among British officials that there was nothing left for them to do in Palestine.[226] Perhaps the ultimate achievement of the Arab Revolt was to make the British sick of Palestine.[227] Major-General Bernard "Monty" Montgomery concluded, "the Jew murders the Arab and the Arab murders the Jew. This is what is going on in Palestine now. And it will go on for the next 50 years in all probability."[228]

Historiography

The 1936–39 Arab Revolt has been and still is marginalized in both Western and Israeli historiography on Palestine, and even progressive Western scholars have little to say about the anti-colonial struggle of the Palestinian Arab rebels against the British Empire.[229] According to Swedenburg's analysis, for instance, the Zionist version of Israeli history acknowledges only one authentic national movement: the struggle for Jewish self-determination that resulted in the Israeli Declaration of Independence in May 1948.[229] Swedenburg writes that the Zionist narrative has no room for an anticolonial and anti-British Palestinian national revolt.[230] Zionists often describe the revolt as a series of "events" (Hebrew מאורעות תרצ"ו-תרצ"ט) "riots", or "happenings".[230] The appropriate description was debated by Jewish Agency officials, who were keen not to give a negative impression of Palestine to prospective immigrants[231] In private, however, David Ben-Gurion was unequivocal: the Arabs, he said, were "fighting dispossession ... The fear is not of losing land, but of losing the homeland of the Arab people, which others want to turn into the homeland of the Jewish people."[17]

British historian Alan Allport, in his 2020 survey of the British Empire on the eve of the Second World War concludes that murderous incidents like al-Bassa:

were outrageous precisely because they were unusual. On the whole, the British Army and the various colonial gendarmeries that worked alongside it in the 1920s and 1930s behaved fairly well—certainly with a good deal more self-restraint than security forces of other imperial states. There is nothing in the British record in Palestine to compare with the devastating violence of the Rif War in Spanish Morocco for instance or the Italian pacification of Libya, both of which involve killing on a vastly greater scale. Many British soldiers behaved impeccably in Palestine during the Arab revolt.[232]